IV.

Post-NAS Report Legal Change

The legal response to research in the eyewitness area has been striking: change has been steady, and the pace of change has been more pronounced in the six years since the NAS report was released. We describe here how state courts have reconsidered traditional rulings regarding eyewitness evidence, states have enacted statutes requiring changes made in lineup procedures, and still additional states have adopted model policies, or otherwise promoted new practices by law enforcement. We provide a summary of these developments in law and practice.

A.

State Court Rulings on Admissibility of Eyewitness Evidence

First, there has been striking change in the courts. In recent years, although the U.S. Supreme Court has not revisited its 1976 Manson v. Brathwaite test, a growing number of state courts have departed from the federal due process rule, relying on the research that has developed in the intervening decades.1Thomas Albright & Brandon L. Garrett, The Law and Science of Eyewitness Evidence, 101 Boston U. L. Rev. __ (forthcoming 2021), at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3675055. The Supreme Courts of Alaska,2Young v. Alaska, 347 P.3d 395, 414 (Alaska 2016) (describing how “[t]he past few decades have seen an explosion of additional research that has led to important insights into how vision and memory work, what we see and remember best, and what causes these processes to fail.”) (citing Identifying the Culprit, supra note xxx, at 69). Connecticut,3State v. Guilbert, 306 Conn. 218, 49 A.3d 705, 720–22 (2012). Hawaii,4State v. Cabagbag, 277 P.3d 1027, 1035–38 (Haw.2012). Oregon,5State v. Lawson, 352 Or. 724, 291 P.3d 673, 685 (2012) (en banc). Utah,6State v. Clopten, 223 P.3d 1103, 1108 (Utah 2009). and Wisconsin,7State v. Dubose, 285 Wis.2d 143, 699 N.W.2d 582, 591–92 (2005) (finding showups inherently suggestive in light of “extensive studies on the issue of identification evidence”). have relied directly on scientific research in rulings changing how eyewitness evidence should be.8Young v. State, 374 P.3d 395, 414 (Alaska 2016) (collecting citations); State v. Guilbert, 306 Conn. 218, 49 A.3d 705, 720–22 (2012).

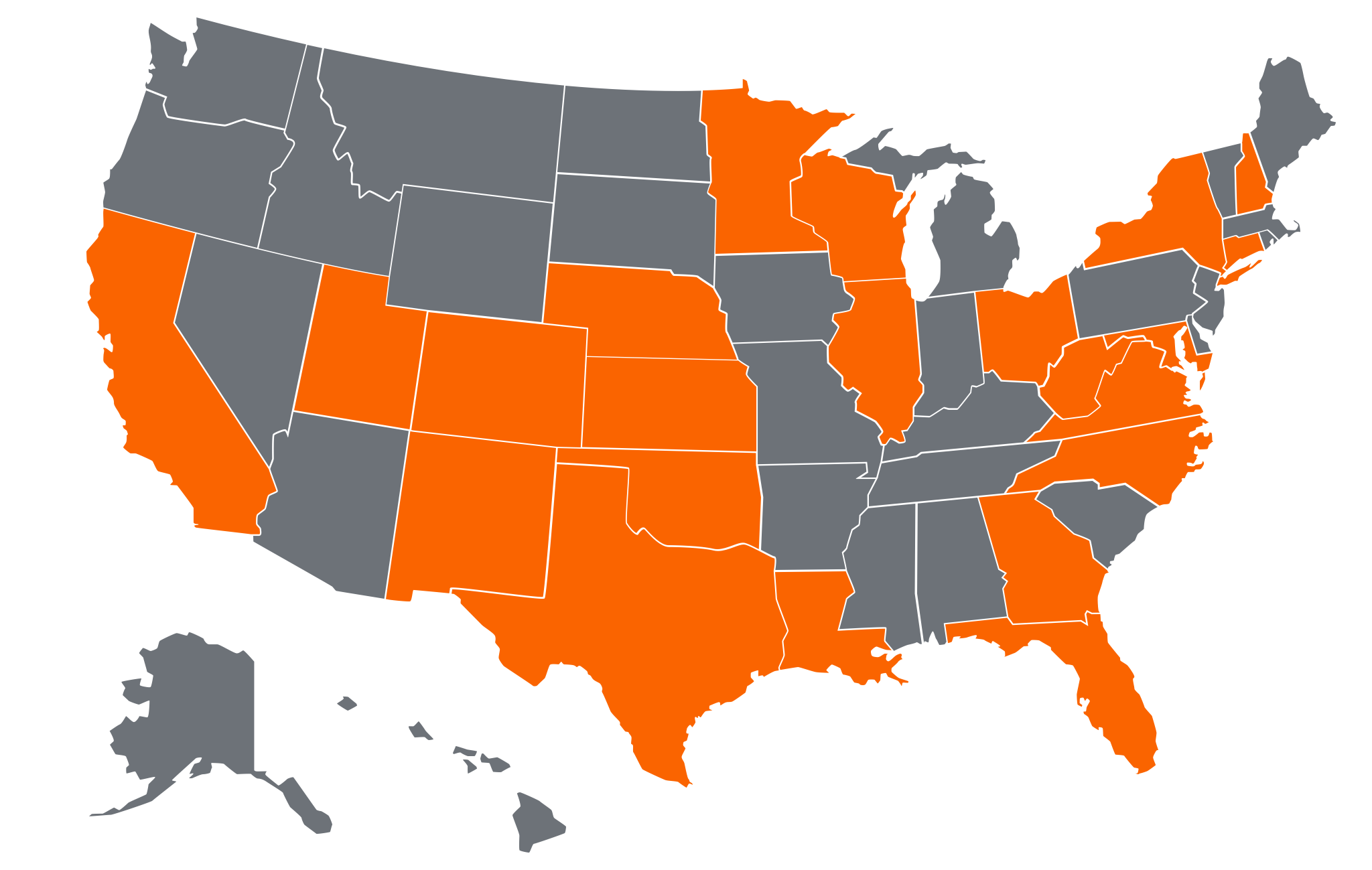

![]() State Supreme Courts that have revised the eyewitness admissibility framework:

State Supreme Courts that have revised the eyewitness admissibility framework:

Alaska

Connecticut

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Kansas

Massachusetts

New Jersey

New York

Oregon

Utah

Vermont

![]() State Courts that have revised jury instructions to reflect eyewitness memory research:

State Courts that have revised jury instructions to reflect eyewitness memory research:

Alaska

Connecticut

Florida

Hawaii

Massachusetts

Missouri

New Jersey

Ohio

Pennsylvania

Utah

Virginia

Perhaps most prominent and ambitious judicial action was the ruling of the New Jersey Supreme Court in New Jersey v. Henderson, which revised the entire legal framework for reviewing eyewitness evidence.9Henderson, 208 N.J.208 (2011). The decision set out a framework in which pre-trial hearings must examine eyewitness identification evidence, to assess its reliability pre-trial. A defendant must show evidence of unreliability and the state must counter with evidence of reliability. In response, the judge may consider remedies, including jury instructions at trial.10Id.

In 2016, the Alaska Supreme Court revised the Manson test, and adopted a more detailed framework, asking judges to focus on both estimator and system variables, as in the Henderson decision, and adjudicating these questions pre-trial, including with the benefit of expert testimony to explain how those variables may apply to different factual situations.11Young v. State, 374 P.3d 395 (Alaska 2016). If the defendant meets this burden, “the trial court should suppress the evidence—both the pretrial identification and any subsequent in-court identification by the witness.” If the defendant does not, however, then “the court should admit the evidence and provide the jury with an instruction appropriate to the context of the case.”12Id. at 427. The approach, thus, resembles the type of functional framework adopted in New Jersey. In 2018, in State v. Harris, the Connecticut Supreme Court, adopted a framework much like that in New Jersey (noting the “overlap” with that approach), holding expert testimony may be valuable, and “it may be appropriate for the trial court to craft jury instructions to assist the jury in its consideration of this issue.”13State v. Harris, 191 A.3d 119, 145 (Conn. 2018).

Adopting a slightly different approach, the Hawaii Supreme Court trial ruled in 2019 that “courts must, at minimum, consider any relevant factors set out in the Hawaii Standard Instructions governing eyewitness and show-up identifications, as may be amended.” Thus, the Court did not set out a series of factors, as the New Jersey Court did, but rather set out jury instructions that may be changed over time.14State v. Kaneaiakala, 450 P.3d 761, 777 (Haw. 2019). Tracking the New Jersey focus on system variables, the court also emphasized the importance of suggestion: “trial courts must also consider the effect of the suggestiveness on the reliability of the identification in determining whether it should be admitted into evidence.”15Id. at 778. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in 2015, “review[ed] the scholarly research, analyses by other courts, amici submissions,” and the report by a Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Council Study Group on Eyewitness Identification.16Commonwealth v. Gomes, 470 Mass. 352, 22 N.E.3d 897, 905, 909–10 (2015). The court recommended judges provide a set of more concise jury instructions on eyewitness identification evidence.17Id. The approach similarly includes a range of research-informed factors, but with adopting jury instructions that are more manageable in length.

In contrast to these approaches, which rely on a multi-factored standard for admissibility and instructions for educating jurors, the Oregon Supreme Court has endorsed review of reliability of eyewitness evidence relying on a general Rule 403 analysis under the Oregon Rules of Evidence.18State v. Lawson, 291 P.2d 673 (Or. 2012). The Oregon Court identified two problems with the prior framework: the “threshold requirement of suggestiveness inhibits courts from considering evidentiary concerns;” and the “inquiry fails to account for the influence of suggestion on evidence of reliability.”19Id. at 746-48.

While the federal courts have not adopted new constitutional tests, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals convened a Task Force on Eyewitness Identifications that issued a detailed report in 2019.20Third Circuit Task Force on Eyewitness Identifications (2019). That report was not binding, but rather made recommendations to law enforcement, advocates, and courts, including recommendations regarding conducting lineups, videotaping lineups, documenting witness confidence, blind administration, and amended jury instructions, as well as continuing education materials for lawyers.

In addition to these rulings, the past decade has also seen much change in jury instructions regarding admissibility that courts adopt in states. Fifteen states have recently revised their jury instructions: Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Kansas, Maine, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Utah, and Virginia. As noted above, Hawaii, Massachusetts and New Jersey have more substantially revamped their jury instructions, while other states made more modest changes. Sixteen remaining states do not provide separate instructions on eyewitness evidence specifically and instead instruct jurors to generally judge witness credibility.21 Those states are Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Texas, Rhode Island, and Wyoming. Rhode Island has no pattern criminal jury instructions. No strong evidence shows these jury instructions accomplish their aim to better educate jurors regarding the strengths and weaknesses of eyewitness evidence, particularly given the great weight that jurors place on the courtroom confidence of an eyewitness.22See Garrett, Dodson, Kafadar, Liu, and Yaffe, supra note xxx. Indeed, the most detailed instructions, adopted in New Jersey, have not been found effective in mock jury studies; nor have the shorter Massachusetts instructions.23Id. See also Brandon L. Garrett, Judging Eyewitness Evidence, 104 Judicature 31 (2020). More pointed instructions focused on the reasons why courtroom confidence of eyewitnesses should not be relied upon have been found more effective.24Id. As a result, it is far more important to ensure that identification procedures are conducted properly in the first instance, and to address the courtroom confidence problem by limiting or eliminating such in-court identifications and statements.

B.

State Statutes

Change has also occurred in state law, through the enactment of legislation that more directly targets the practices used by police agencies. To date, twenty-four states have adopted legislation regarding eyewitness identification procedures. These statutes were often enacted to assure uniformity in adoption of best practices. Thus, Minnesota adopted a statute in 2020, after a survey by the Minnesota Police Chiefs Association and Sheriffs’ Associations found that half of law enforcement agencies did not even have written lineup policies.25Staff, Minnesota Adopts Eyewitness ID Law to Prevent Wrongful Convictions, Davis Vanguard, May 26, 2020. Most of those states regulate procedures to be used, focusing on key features of a sound policy as outlined above, including blind or blinded lineups, clear written instructions, and documenting the confidence of an eyewitness.

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Florida

Georgia

Illinois

Kansas

Louisiana

Maryland

Minnessota

New York

North Carolina

Nebraska

New Hampshire

New Mexico

Ohio

Oklahoma

Texas

Utah

Virginia

West Virginia

Wisconsin

C.

Model Practices

In recent years, professional policing organizations, such as the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), Major City Chiefs Association, and Commission on Accreditation of Law Enforcement Agencies (CALEA), have taken active roles in promoting best practices, including through model policies.26International Association of Chiefs of Police, National Summit on Wrongful Convictions: Building a Systemic Approach to Prevent Wrongful Convictions 10 (August 2013); CALEA Law Enforcement Standard 42.2.11; IACP Model Policy, Eyewitness Identification (2010). Twenty-nine states and the federal government have voluntarily adopted such policies regulating eyewitness identifications. The model policies generally require blind or blinded lineups, clear written instructions, and documenting confidence; many recommend videotaping.

Thus, in conclusion, a large body of state court rulings, jury instructions, state statutes, and model policies, have resulted in substantial changes to law enforcement and judicial practice, particularly in recent years. As discussed below, however, important gaps remain in implementation of many longstanding, core recommendations regarding eyewitness evidence.

Next: Future Directions in Eyewitness Research and Policy >